My first glaciated summit was Mt. Hood three years ago. My favorite part of that climb was the view of Mt. Jefferson. It was a perfect pyramidal summit rising out of the clouds. I knew I’d need to go up it one day to round the experience out. I wanted to see the view from the other side of the table too.

On a barely-thought-out whim, Ben and I decided to climb Mt. Jefferson via the Southwest Ridge car-to-car this weekend. We wanted to achieve the perfect balance of speed and safety. So, I brought a 60m half-rope, two pickets, 4 alpine draws, a Blue Totem Cam, Black Totem Cam, 5 nuts, and a quad-length sling as our rack. We each had mountain boots, steel crampons, and two tools as well. From all the reports we read, it seemed to be nothing more than a moderate snow traverse and then 3rd/4th class to the summit. We expected this rack to be overkill, but we wanted options. It would suck to trudge up only to turn around.

We didn’t bother getting permits for the Pamelia Lake Trailhead. I wouldn’t recommend any other climber deal with that hassle either. The fact that we need permits to use our public lands — especially day use — is a completely different rant. But if parking at the trailhead, all that’s required is a park pass or forest pass on the vehicle. There’s no way to be identified as a permit holder based on the vehicle. And, on the slim chance you run across a ranger on a trail, you can say you came from the Woodpecker Trailhead.

On Friday evening, we pulled into the trailhead. We divvied up group gear, packed our bags, and went to sleep in our vehicles. At 10:30 p.m., two hours of sleep in, we woke up. I chugged a can of cold brew coffee, and Ben had some espresso. We set off into the night.

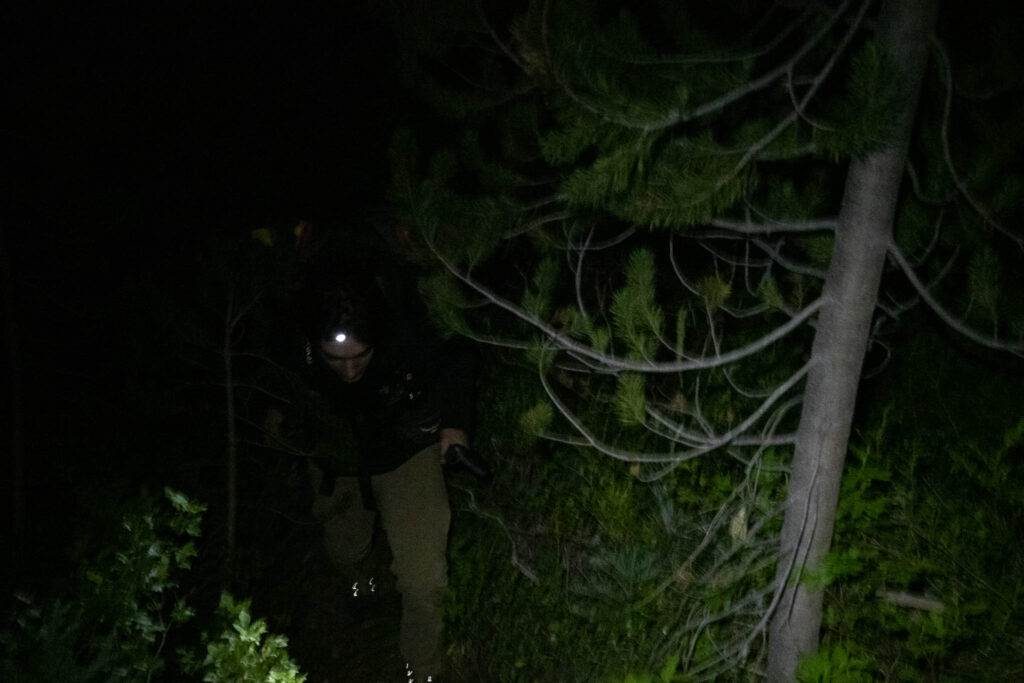

The miles went by at light speed. Something about hiking by the light of a headlamp makes you fly. Before we knew it, we racked up 1,500 feet of gain and were 15 minutes into the PCT. Now the bushwhacking would begin.

Following a GPS track, we turned into the thick brush. We’d need to follow a shallow but incredibly steep gully to breach treeline. As soon as we turned, the grade became at least 45 degrees for several hundred vertical feet. We found a shallow use path in some parts which saved us from the brush. For the majority of time though, we weren’t on that, and bumbled through dense brush. It was the classic Cascade experience — done by the light of a headlamp to boot.

After a particularly rough stretch of brush, we took a break. I plopped my backpack down on the ground and I heard a loud crack. I turned my backpack over and saw that I crushed my helmet. The first casualty of the day. Oh well. I decided to continue and hope no rocks would hit me. I reckoned I could still make the helmet work with my hood cinched down.

Soon, we reached wider-spaced old-growth trees. They allowed faster travel. Then, we reached a subsidiary ridge-line. We followed that for several hundred more vertical feet before breaking treeline.

After breaking treeline, we’d have to meet the Southwest Ridge by climbing 1,000 feet up the Northwest Face of the Southwest Ridge. I was glad it was dark because the very sight of the slope would’ve been enough to render us sick. It was 1,000 feet of kitty-litter scree. With our heavy packs, this was miserable. But, we pushed through it. An hour later, we met the Southwest Ridge.

We were 4,000 vertical feet into the climb now. I was feeling great. I’ve made my nutrition better for car-to-car pushes, and I got this just right. I had some caffeine gels, some food, a liter-and-a-half of Powerade, and two liters of water with me. This was just right, and I was feeling strong. We were more than halfway to the summit now.

While the the face was miserable, the rest of the way up wasn’t much better. It was a mix of kitty-litter scree, teetering blocks, “baby-head rocks”, and everything in between. Nothing was solid and progress was difficult. Even though the summit was a couple of miles away, we had to zig-zag, scramble, and meander our way up to make progress.

All the while, we heard rockfall pound through the ravine to our north — the Mill Creek drainage. Mt. Jefferson truly is crumbling into oblivion.

Soon, the sun started to rise. We were treated to a spectacular sight. Alpenglow began to shroud the line of volcanoes to the south. The classic pyramid shadow began to develop too. It was sublime.

Some more miserable trudging brought us to about 9,000 feet of elevation. The summit was a stone’s throw away. But now, the terrain was near-constant class 3 scrambling on loose blocks. With our heavy backpacks, it was exhausting. At 9,500 feet, we swapped into our mountain boots. That took five pounds off our back. I left my approach shoes here to save weight, but Ben packed his shoes with him.

We marched up the Southwest Ridge, which merged into the South Ridge a little after 9,500 feet. The views were phenomenal. As a plus, our pre-midnight start brought us to the upper mountain early. We had a decent time margin to reach the summit and return before the sun and the heat would increase the danger of the peak. With our margin, we knew we would make it.

We rounded by a tiny bump in the ridge, and the Red Saddle was right there. The summit was only 300 or 400 feet away now. We were at the home stretch. The traverse looked great too, with some of the climbing in a sheltered moat as well. Even better: It seemed that there was enough exposed rock to protect with nuts and cams instead. That would be a lot faster than banging in pickets.

The decision of whether to protect or solo the traverse was difficult. On one hand, soloing would’ve been faster and would be within our abilities. On the other hand, this area is exposed to dangerous rockfall. If either of us was hit by a rock, it would be a death sentence. While a roped traverse would keep us in the danger zone longer, we felt the safety of a rope was worth it.

We harnessed up, racked up, and roped up. I managed to make my helmet work by putting on my hard-shell and cinching the hood tight over it.

We built the first anchor with the rope tied around a solid boulder at the beginning of the traverse. I led, traversing the snow, and then entered the moat. The rock was loose and sketchy, but I found a solid placement for a Black Totem as the first piece. I continued traversing. Some of the route was in the moat, and some was on the steep snow. Part of the moat was a deep gorge which wasn’t climbable, hence the detours onto the face.

I reached the end of the 60m rope and we started to simul-climb. We did so for about 60 feet before I reached the end of the snow. I struggled to find something to build an anchor with. There was almost nothing. All the rock here was loose dinner plates, and nothing would have held. I did find a solid rock horn which I girth-hitched a sling around. I then placed a shitty cam to keep the direction of pull constant. Then, I brought Ben over. That probably would’ve held, but I’m glad we didn’t test the protection.

The summit was in sight now. The beta I read said we would first need to traverse over to the north, and then go up that way on 3rd and 4th class terrain. From our vantage point, that route looked perilous and loose. The traverse looked sketchy too. Perhaps that goes better when there’s more snow. In the end, I decided to go straight up and follow the point of least resistance.

We each coiled up 20 meters of rope and started simul-climbing again. This terrain was fourth class, but next to nothing was solid. It was perilously stacked dinner plates. I had to work hard not to drop any boulders on Ben. A little way up, he accidentally kicked down a rock. That rock bounced a few times, which caused a few more boulders to release. Then, they pummeled the snow traverse we just crossed. The rocks continued to cascade down the ravine, triggering more rockfall with each bounce. It was pretty somber. I wouldn’t recommend climbing below any parties at all. Thankfully, that doesn’t seem to be a problem. The peak isn’t climbed frequently.

I soon reached the face of the summit pinnacle. I continued up on fifth-class terrain in a sort-of-dihedral. It was low fifth class, but I’m not going to lie, it was unsettling. With 7,000 feet of gain, 2 hours of sleep, mountain boots, and a backpack — it was harder than it felt. Not to mention, everything was loose. With my minimal rock rack and the horrible rock, protecting it was a challenge.

I wasn’t in the mood to simul-climb fifth class with marginal protection, and I didn’t have enough protection to do long pitches. So, I decided to build an anchor wherever I could. I continued, and found a bail anchor around a solid chockstone. The webbing looked frayed, so I backed it up with a sling. I brought Ben up, and then we switched to pitching it out.

I continued leading, placing protection whenever necessary. I didn’t want to weigh any gear placements. So, when I came across another rappel anchor 50 feet later, I built a belay then and there. I didn’t want to venture higher into unknown terrain with no gear and have nothing solid to sling. I brought Ben up, and he ended up taking a fall — which was harmless thanks to the anchor. Glad we didn’t solo it — or simul-climb it for that matter.

I led another pitch, and 80 feet later, I found a few solid boulders. I built a decent anchor with my quad-length sling and brought Ben up.

By now, we’d spent quite a bit of time climbing with all the pitching and simul-climbing. From our vantage point, the summit wasn’t even in sight. Not one to give up, I started leading again. Much to my surprise, 15 feet of fourth class later brought me to the summit. There was a solid rappel anchor right there. So, I built a quick belay and brought Ben up a minute later.

The view was awesome, but we didn’t have time to enjoy it. Every minute spent up there was more danger. And by now, we were too familiar with how loose and unstable the mountain was. I wanted to get the hell off of Jefferson as soon as possible. There was a summit register. We took a minute to spot entries, and there were only a few this entire summer. We didn’t bother signing as I couldn’t find a pen and didn’t want to waste time digging through the box. Then, we took some quick summit photos, and started to setup the rappel.

The first rappel from the summit was a little under 30 meters. That brought us to the second rappel anchor. The webbing there was sun-damaged. So, I threaded some 5-millimeter accessory cord through it as a backup. We did another rappel. This was about 25 meters, and it brought us to the end of the 5th-class and to the beginning of 4th-class terrain.

Since we already had the rope out, I wanted to build another anchor to bring us to the snow traverse. Down-climbing 4th-class dinner plates would’ve been sketchy. I searched and searched, but there was nothing I’d be willing to trust our bodyweight on. Down-climbing was a better choice, and we made it to the start of the snow.

We put our crampons and tools back on. Then, I led us across the traverse. The sun was on it now, but it was still icy. The surface was an inch of saturated snow with front-point-only snow beneath it. I took the time to place some solid protection, with four good placements 50 – 60 feet apart. I got to the end of the rope, and then we simul-climbed 60 feet. I built an anchor with a decent boulder and belayed Ben the remaining distance.

While we were traversing, a party of three popped up at the Red Saddle. They each had tiny backpacks and running shoes on. They watched our traverse, and when we finished traversing, they started to descend.

We still weren’t safe though. I coiled the rope as fast as I could, then traversed 100 feet from the belay to the Red Saddle. We were finally free of overhead hazards. It was for the best too. Ben mentioned that rocks were whizzing by his head as he belayed me. The mountain had spat us off just in time.

We could finally relax and take stock of our situation. We had over 7,000 feet of descending to get back to the cars. And, we were low on water. I had 750 ml left, while Ben had 250 ml. Thankfully, there was snow on the way down we could melt against our backs in our hydration sacks. We would be fine, but we would suffer.

We put our climbing gear in our backpacks, shouldered the extra weight, and began to march down. The first 800 feet of descending was slow down-climbing on loose rock. Pretty exhausting.

Then, we started to find consistent scree which we could ski down in parts. We continued descending the ridge, but a little way down, I got a fishy feeling. Where were my shoes? I checked my GPS, and we made a mistake and continued on the South Ridge — not the Southwest Ridge. Darn. I decided my shoes were a lost cause. No way was I going to ascend back up on that horrific scree.

We didn’t have to follow this through though. We’d be able to meet the Southwest Ridge by holding a downward traverse. We started to traverse, but then found that the face between the ridges had good scree for descending. We stayed on the face to save time on the descent. We had to be ginger in a few spots, but it was much faster than what the Southwest Ridge would’ve been.

Near the point where we’d need to join the SW ridge again, there was a snowfield with a small pond in it. Water! We’d be fine. Ben was mistrustful of the water quality, but I thought it’d be fine. The only source was snow-melt after all. We were 500 vertical feet from the pond, but that went by super slow. It was down-scrambling on loose rock between baby-head and mini-fridge size. The worst combination.

When we made it there, we found dead bugs filling the pond. Yuck. But then, Ben pointed out a spot on the far shore of the pond. I went there and dug into the snow. I found slush a few inches down. I cleared the slush away and we were left gallons of crystal clear water.

Ben came over and we chugged some much-needed water. We each filled up a liter, which we thought would suffice the rest of the way down.

We continued descending. Unfortunately, we had to ascend 300 feet from the pond to meet the Southwest Ridge again. We met the ridge, and weren’t met with kitty litter scree, but more down-scrambling. We continued down, miserable.

Several hundred feet of descent later came our saving grace. The 1,000-foot kitty-litter-scree face was then and there. We dispatched that 1,000 feet in 20 or 30 minutes, scree-skiing our way down. It almost made that portion of the climb worth it

We reached the subsidiary ridge-line and continued in dread. Our next obstacle would be the crux — the bushwhack.

We left that mini ridge-line and descended into the trees. The going was more straightforward than we thought. It was a little brushy, but not bad at all. Now that we had daylight, we could pick an easy way down.

Then, our luck ran out. The slope abruptly rolled over to a 100% grade for the second half of the bushwhack. I saw that our GPS track was a couple of hundred feet away. But, our going was good so we decided we’d ignore the track and follow the path of least resistance.

We trudged downhill but did not find any path of least resistance. Instead, we found 10-foot-tall impenetrable plants. The slope was so steep that traversing would’ve been futile. Instead, we had no choice but to use our bodyweight to violently power through. All the while, pollen, plants, and spiderwebs rained down our faces and into our shirts. We got stuck a dozen times each, and the only escape was to break our way out. Mother Nature wasn’t a fan of us that day.

I don’t know how long we spent thrashing around, but an eternity later, we reached the PCT. The joy was indescribable. We were at the home stretch now.

Our one liter of water from the pond several hours prior wasn’t enough. Now, we were dehydrated, and we had 4 miles and 1,500 feet to go. It would be on a trail at least.

Tempting waterfalls and rivers surrounded our hike down. We didn’t want to risk drinking it without a filter, but I got desperate a mile from the trailhead. I clasped a handful of water from a river. The liquid turned brown from the gunk in my hands and there were bugs in it too. That turned me off and I continued.

Soon, we reached the vehicles. The party from the Red Saddle was waiting. They asked us for beta and about the rack we brought. I also inquired why they turned around at the Red Saddle. They said that they hoped to pull it off with micro-spikes and trail-runners. When they saw us with tools, crampons, boots, a rope, and protection — plus the state of the traverse — they decided not to continue.

A shame that they needed to turn around so close, but it would’ve been so efficient if they pulled it off. With no boots, crampons, or ice tools — that’s at least 7 pounds saved per person. With no rope or protection, that’s more than 10 pounds saved per person. Over 7,000 feet of gain, that’s a lot of energy conserved. A part of me wonders if we could’ve passed our gear to them at the saddle. Then, they could’ve summited, and then carried our heavy equipment down for us! That would’ve been the ultimate win-win.

We checked the clock, and we were at 20-and-a-half hours. My longest day was 19 hours, so this was my new record. With pitching out the climb and getting lost, the hours flew by.

Exhausted, we chugged some water. Ben drove home, and I drove my home back to Bend.

I wanted to take a shower, but it turned out that the Bend Planet Fitness changed its weekend hours to close at 7 p.m. Oh well. Instead, I got some much-needed calories from McDonalds and went to sleep.

Sounds like a spicy trip. Glad you both made it back safe. Climbing on dishes doesn’t sound fun. Great write up!